Price-based

Prices for resources and waste management which don’t reflect associated negative externalities can therefore incentivise the over-consumption of resources and over-production of waste (Bleischwitz, 2010; Defra, 2011). Price and market-based instruments (PMBIs) seek to correct this and incentivise outcomes by directly affecting payoff structures via the price system (Stavins, 2001). This is often framed in terms of internalising ‘externalities’ i.e. costs to society not already captured in market prices (Pigou, 1920; Coase, 1960).

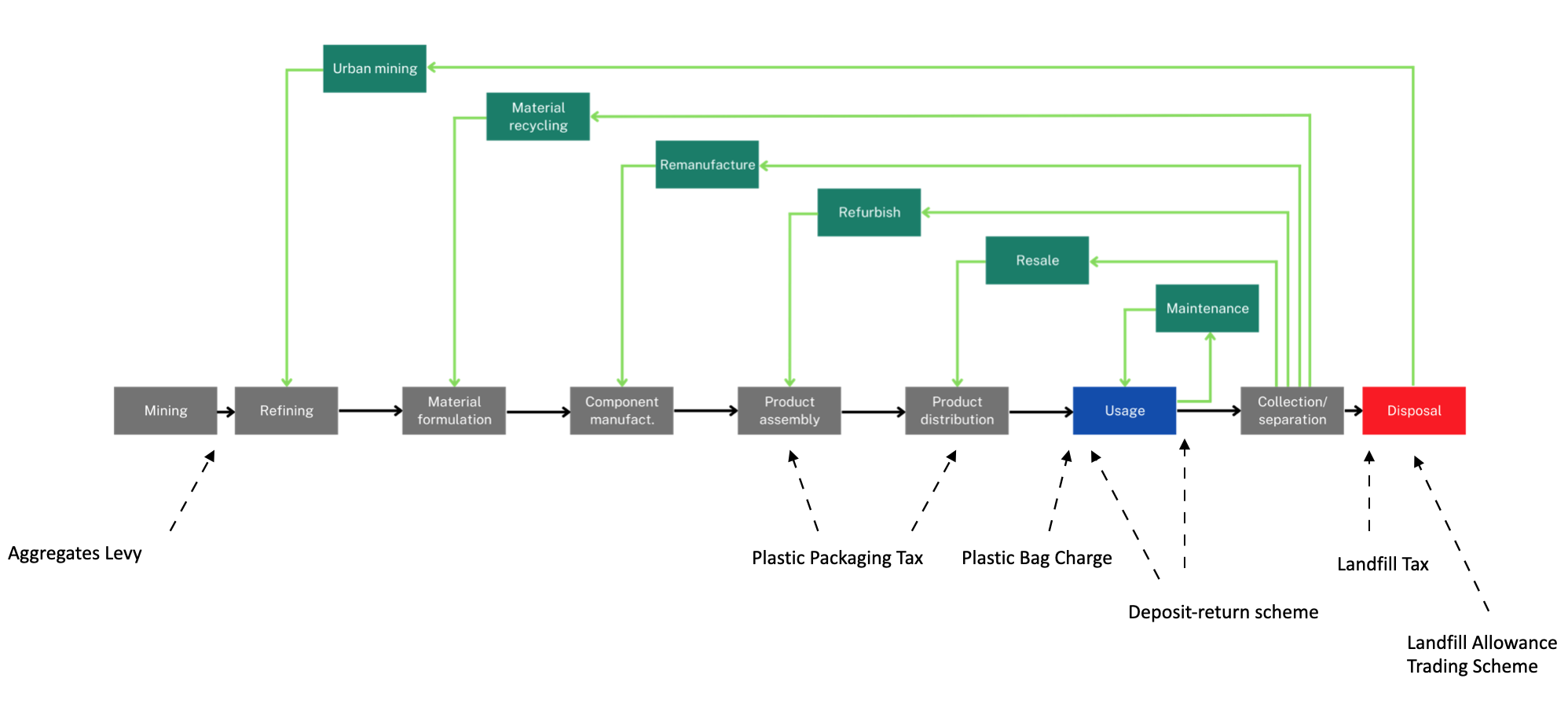

Several PMBIs levied on material flows have been applied across UK value chains to date, including on: the extraction of certain non-metallic minerals (Aggregates Levy); plastic packaging not meeting a 30% recycled content threshold (Packaging Tax); the consumption of single use carrier bags (SUCBs); and certain waste disposal routes (Landfill Tax). PMBIs are considered for nearly all environmental problems raised, however they may not work well under every set of circumstances (Stavins, 2003).

The effectiveness and efficiency of PMBIs are based on the ‘rational polluter hypothesis’, assuming that regulatees are aware of their marginal costs and benefits and that in response to the instrument, regulatees will switch to less environmentally-intensive production or consumption. Before PMBIs are introduced, any fiscal privileges to damaging environmental uses should be removed as these can undermine policy effectiveness and lead to counterproductive transfers (Scott, 1997).

How the tool works and current applications in the UK

Administered prices (sometimes referred to as ‘non-market-based economic and fiscal instruments’ UNFCCC, 2014) involve introducing a price where one did not previously exist or modifying an existing price on goods or services to better reflect otherwise externalised social costs in market prices and in doing so, alter behaviour (Pigou, 1920). Sub-types include:

Taxes1 relevant to the CE include those levied: on (characteristics of) materials or products within the economy; and on the use of the environment as a source (such as a tax on primary material extraction or transformed inputs such as energy) or sink, whether for solid waste (such as a tax on landfilling activities) or gaseous wastes (such as levied on greenhouse gas emissions). In addition, the tax regime covering relevant factor markets such as labour or capital can be altered such as via relief schemes to incentivise activities which indirectly impact environmental use such as a reduction in VAT charged on repair services.

Current applications in the UK include the:

Aggregates Levy - Introduced in the UK in 2002, a tax levied on the commercial exploitation of rock, sand and gravel in the UK (Ettlinger, 2022). Current rates are £2.03 per tonne, with proposals for separate systems in some DAs e.g. the proposed Scottish Aggregates Levy;

Plastic Packaging Tax - Introduced in the UK in 2022, a tax on plastic packaging with less than 30% recycled content. Current rates are £210.82 per tonne;

Landfill Tax - Introduced in the UK in 1996, a two-tiered tax on the treatment of waste by landfill. Current rates are £102.10 per tonne for the ‘standard rate’ (including municipal waste) and £3.25 per tonne for the lower rate covering inert materials;

Climate Change Levy - Introduced in the UK in 2001, a tax on energy delivered to non-domestic users. Current rates are £0.00775 per kWh electricity, £0.00672 per KwH gas and £0.02175 per kg LPG.

Sometimes distinguished from taxes on the basis of being a ‘requited’ payment i.e. a good or service is received in exchange (ONS, 2019), fees levied on the use of the environment or a proxy of it and whether as a flat fee or payment per unit. Current applications in the UK include the:

Plastic Bag Charge - Introduced in the UK in October 2015, a charge levied on single-use carrier bags sold at the level of 10p per bag since 2021, up from 5p when first introduced (2015);

A range of additional charges levied by the Environment Agency; and

Congestion and emissions charges - Charges to enter ‘clean air zones’ with an emissions generating vehicle throughout the UK.

Front end fees added to a transaction, combined with a rebate conditional upon a sought action being undertaken. Prospective applications in the UK include the:

- Deposit-Return Schemes – Planned for introduction in Scotland in 2025 and in 2027 in England, Wales & N. Ireland, a charge-rebate system consisting of front-end charges on single-use drinks containers combined with a rebate upon their disposal at collection points. This is intended to incentivise correct end-of-life treatment and significantly reduce littering.

Deposit Return Schemes (DRS) have proven to be highly effective tools for combating littering and fostering recycling. The global deposit book from reloop gives a comprehensive summary of DES schemes in place (Reloop, 2022). Among global leaders, Norway, Germany, and Lithuania stand out for their exemplary DRS models. These countries have achieved success through innovative system designs, high collection rates, and broad public engagement. Norway, Germany and Lithuania all have slightly different approaches for example the deposit management organisation (DMO) for Norway is a charity organisation, in Germany is industry led and Lithuania uses a non-profit organisation, however all have achieved over 90% return rates in their schemes (Reloop, 2022).

We have assessed the deposit return scheme according to the criteria for instrument selection section to give an overview of the system dynamics for DRS. The following is a summary of our findings from a review of available literature, giving a balanced assessment of each selection criteria.

Environmental Effectiveness

Deposit Return Schemes (DRS) have proven to be powerful tools in reducing plastic pollution and enhancing recycling efficiency. Forecasts from Defra project that the implementation of DRS in the UK could lead to an 85% reduction in litter, underscoring its potential to drastically minimize plastic waste (Defra, 2024a). Evidence from Norway reinforces this projection, where plastic bottle collection rates consistently surpass 90%, highlighting the real-world success of well-designed systems in reducing environmental pollution (March et al. 2024a). Corporate initiatives such as Lush’s eco-design policies demonstrate how private sector actions can enhance waste reduction efforts alongside public recycling schemes (March et al. 2024b). There is potential for DRS to reduce carbon emissions, with many reports suggesting the increase in recyclate quality can improve recycling and decrease reliance on virgin fossil feedstocks (March et al., 2024a,c,d. Rhein et al., 2021. Tudor & Williams, 2021. Karasik et al., 2020. Defra, 2021a,b. Defra, 2024a,b. Kukenthal et al., 2023. Picuno et al., 2024. Eunomia, 2010. Systra, 2021.). Diverting waste from landfill and incineration can reduce emissions and mitigate pollution to the natural environment.

However, establishing the necessary infrastructure, such as reverse vending machines and logistics networks, can lead to a temporary increase in carbon emissions. There are criticisms that DRS does not promote circular economy by proliferating the use of single use plastics and materials and actively encouraging the production of single use materials to be in line with DRS.

Financial Cost to the Public Sector

Deposit Return Schemes (DRS) offer potential long-term savings for the public sector. According to Defra, the UK could save an estimated £11.4 billion over time through reduced litter cleanup and landfill costs (Defra, 2024 a,b). Additionally, private sector financing plays a critical role in offsetting public costs by bearing the majority of the costs when in line with political frameworks such as extended producer responsibility. Unredeemed deposits also contribute to the funding of the scheme.

Implementing DRS involves high initial costs for public sector finance, through new reverse vending machine infrastructure and collection services. Furthermore, the system requires ongoing administrative oversight, including managing deposit flows and ensuring compliance. These administrative costs can strain public sector resources if not efficiently managed, highlighting the importance of careful planning in DRS implementation.

Long-Run Effects

DRS can drive significant behavioural change by embedding sustained recycling habits in consumers and willingness to adapt more sustainable practices. DRS can also drive demand for increased reprocessing with a consistent high quality recyclate feedstock. If high return rates are sustained there will be a long-term environmental benefit through reduction in pollution and diversion from landfill and incineration.

As return rates stabilise the revenue from unreturned deposits will be lost, which could result in a decline in participation from industry, particularly small business owners.

Distributional and Equity Effects

The deposit refund system ensures that all participants, including low-income groups, can reclaim their deposits, promoting fairness and equity in recycling participation. Integration with extended producer responsibility can ensure consumers do not take on the financial burden.

Despite these benefits, DRS can impose operational burdens on retailers, particularly small businesses. Retailers are required to manage container returns, which can be costly and logistically complex. Additionally, deposit schemes may disproportionately affect those with limited access (e.g. rural areas, low income groups and disabilities) if the upfront deposit costs are not effectively offset by timely redemption and easy access is not made available to all.

Spillovers

A successful DRS model (e.g. Norway), can be used as an example of best practice for other countries to model and approach for other policies. The use of DRS can also complement better waste management practice and long-term reduction of waste for materials in scope. However, the inclusion of DRS can disrupt kerbside collections and reduce the value of kerbside recycling, causing a financial burden on local councils. For the UK, the devolved administrations have differing scope for DRS creating logistical complications for cross-border collection.

Can extend to the scale of environmental impact bonds paid by companies prior e.g. to non-renewable resource extraction, rebated minus any damages once cleaned up (Costanza and Perring, 1990).

Tax relief involves adjusting existing taxes to reduce disincentives to particular behaviours. Applications in the UK include the:

- Enhanced Capital Allowances for water and energy-saving technologies - A form of tax relief, currently used in the UK to incentivise the use of water-saving and energy-saving technologies in the past

Subsidies are a payments to an actor either to not undertake environmental bads or to subsidize the provision of environmental goods. These can take the form of lump sums e.g. for capital costs or per unit subsidies for desired results. Subsidies differ from grants which are generally issued for specific purposes. Applications in the UK include:

Boiler Scrappage Scheme - Introduced in 2010, the scheme aimed to encourage the replacement of old boilers with newer more energy efficient ones

Feed-in tariff scheme for renewable energy sources - Introduced by Department of Energy and Climate Change and Ofgem from 2010 to stimulate the uptake of renewable energy sources in order to combat climate change and improve energy security.

Figure 1. Example of current, historic and prospective UK price and market-based instruments placed in relation to point of introduction along the value-chain.

Performance assessment

Environmental effectiveness

The effectiveness of PMBIs depends on their ability to alter the economics of production, purchasing and use choices. PMBIs are most effective for products whose demand or output is sensitive to price change i.e. demand is elastic.

Material inflow taxation and charges

In theory, increasing the price of primary resources can be expected to reduce the environmental pressures associated with their consumption. This can occur through: 1) reducing the use of resource inputs into production and consumption processes; and 2) driving input substitution away from primary materials towards those secondary (Government Office for Science, 2014).

The UK Aggregates Levy introduced in 2002 had the dual aim of reducing the negative environmental impacts of quarrying and increasing the recycling rate of construction materials by making the costs of virgin material inputs more costly (Ettlinger, 2022).2 Between 2002 and 2018, total aggregation consumption has fallen while the share of aggregates from secondary sources increased (MPA, 2019) - implying also an absolute decoupling of construction industry output from primary material input. However, these impacts are difficult to attribute to the levy alone (Ettlinger 2022), with secondary aggregate consumption on an upward trend prior to the introduction of the Levy, and potentially also linked to the Landfill Tax (introduced in 1996) which encouraged the creation of secondary markets.

A 2011 meta-study of virgin material taxation schemes found these reduced the domestic supply of virgin materials when in place, but often only led to limited increase in the use of recycled materials as virgin materials could be sourced overseas (Söderholm, 2011).

Recycled and secondary materials in total aggregates sales in Great Britain (Million tonnes) (MPA, 20 )

Data published by Wrap showed 12.2 billion single-use carrier bags (SUCB) were used by customers across UK supermarkets in 2006. Wales introduced a 5p charge per SUCB in 2011, followed by N. Ireland in 2013, Scotland in 2014 and in 2015 in England through the statutory instrument Single Use Carrier Bags Charges (England) Order 2015 No. 776. At the time of introduction, the charge in England was expected to save GBP60m savings in litter clean-up costs and GBP13m in carbon savings (Centre for Public Impact, 2016).

The charge on single use carrier bags in England - initially introduced at 5p and since 2021 increased to 10p while being extended to all shops, has seen a significant decrease in the number of single use bags issued by retailers of approximately 80% (Defra, 2022).

Bags issued by reportees in England, by bag type (million) (Defra (2022)

End-of-life taxation and charges

The Landfill Tax was introduced in the United Kingdom in 1996 and applied to all waste disposed of at a licensed landfill site in an attempt to better reflect environmental costs of landfilling in its price, and in doing so, reduce waste entering landfill and associated environmental impact. The tax has since been devolved to Scotland and Wales (OBR, 2023).

A review shortly after the introduction of the tax found it had led to a modest reduction in waste to landfill from industry, but not by households (Morris, Phillips and Read, 1998) and that quantities of waste landfilled remained relatively stable between 1996 and 2003 (Elliot, 2016). With annual rate increases, LACW sent to landfill in England fell by an estimated 90% between 2000 and 2021, while total waste landfill (including non-household waste), has also fallen albeit at a slower pace.

A 2021 study by Panzone et al.using a ridge-regression approach, found the tax has been effective in shifting waste generated to alternative end-destinations than landfill - although to a large extent, this has been incineration.

Landfilled waste by EWC Chapter, England & England and Wales (million tonnes) (Environment Agency, )

Due to the simultaneous effects of other policy instruments, it is difficult to attribute this reduction to the Landfill Tax. A 2023 review of the Landfill Disposal Tax (LDT) in Wales found that increases in recycling since devolution of the tax to Wales in 2017 via the Landfill Disposals Tax (Wales) Act 2017, couldn’t be attributed to the LDT and that other factors including recycling targets had a greater effect on increasing recycling and reuse, while other factors such as zero waste to landfill requirements have been more impactful in driving uptake of alternative technologies.

Summary of responses to a review of the Landfill Tax commissioned by HMT in 2021 found…

A key issue with price-based instrument is that without precise information about the aggregate marginal abatement cost curve or the price elasticity of those subject to a tax, the aggregate environmental outcome of a given tax rate can be difficult to predict and necessitate a trial-and-error approach which can delay environmental improvements (Pearce and Barbier, 2000).

Efficiency

A key proposed benefit of PMBIs is that they can help achieve a particular level of environmental use at the lowest overall cost to society (i.e. are most statically efficient) while providing ongoing incentives to bring down abatement costs over time (Pearce, 2002; Johnson, 1999).

The assumed efficiency benefits of PMBIs are attributed to the rationale that if a price is introduced or adjusted to account for environmental impacts, market participants can be incentivised to reduce their environmental use until the cost of abating a further unit of use equals the marginal benefit of reducing that use in terms of avoided tax payments. Across the sector or the economy regulated, this would translate to environmental users with the least abatement costs reducing use more than those facing steeper abatement costs, thereby helping a given level of use be achieved at least cost in line with the equimarginal principle which assumes that societal welfare is maximised when the net present value of marginal abatement benefits equal that of marginal abatement costs (Baumol & Oates, 1971). These cost reductions have been shown in a variety of cases e.g. SO2 trading scheme under the USA Clean Air Act (Goulder, 2013).

In addition, it is said that if tax revenue accrued by instruments are used by the government to offset distortionary taxes such as those on labour thereby contributing to change in relative factor prices, it can help further improve market efficiency (Vence and Pérez, 2021). The Ex’tax Project argues that “High taxes on labour encourage businesses to minimise their number of employees. Resources, however, tend to be untaxed; they are used unrestrained. This system causes unemployment, overconsumption and pollution”.

The aggregate costs to society (including industry, LAs and the public) of abatement, compliance and administration (Bicket and Salmons, 2013). There has been the following effect on the mining and quarrying sector in the UK, with the following effects on competitiveness… The quarrying of aggregates such as sand, gravel and crushed rock remains the most common type of mineral operation in England ().

Charge-rebate schemes are cited as having potentially high transaction costs.

Where regulation is so stringent all available abatement measures must be taken, market-based instruments aren’t always significantly more cost-effective than standards.

The EU has put into practice the trading theory through the ETS through the Emissions Trading Directive, adopted in 2003 and amended in 2009, which applies to large installations throughout Europe and seeks to reduce their GHG emissions by 40% compared to the baseline by 2030. The EU ETS has been seen as a resounding failure due to several issues: 1) Technical - Overall cap being too generous resulting in the price of permits being too low and leaving little incentive for further reduction through the sale of permits 2) Principled - with issues of fairness related to the permit dissemination approach of grandfathering being questioned and 3) Foundation - with the commodification of environmental quality.

Affordability

The UK government raises over £820 billion a year in receipts, primarily through The income tax, National Insurance contributions (NICs) and value added tax (VAT) which together raise over £470 billion. Environmental taxes make up a relatively small share of this revenue, though nevertheless appear to generate net-revenues for government.

In theory, PMBIs can generate administrative savings in time and money by devolving management decisions from regulators to private decision makers who are better aware of their own abatement costs (Baumol and Oates, 1971; Stavins, 1998).

Revenue generating instruments preferred from an affordability perspective than subsidies. Where subsidies are offered, these need to be financed. For example, a €154 million fund announced in 2023 and set up to cover payments to citizens in France, who will be able to claim €7 for mending a heel and €10-€25 for clothing repairs between 2023-2028. Subsidies present a cost to the government which if funded through general taxation can also be economically distortive.

‘The latest HMRC statistics show that the aggregate levy raised £407m in total receipts in the 2016/17 financial year (a proportion of this has funded the Aggregate Levy Sustainability Fund managed by Natural England). This has been the largest amount collected.’ Resource-related taxation makes up a relatively small share of total environmental taxes in the UK (ONS, 2023).

A 2023 FOI revealed that the PPT has generated over 200 million GBP in the first three quarters following its introduction, with ring-fencing of revenues called for (CIWM, 2023).

Government revenue from environmental taxes in the UK, 1997 to 2021 (ONS, 2022)

Assumed benefits of optimal pricing scenarios in rational choice and welfare maximising frameworks imply likely high information requirements for both the MDC and MAC, which leads regulators to general seek acceptable or improved rather than optimal levels (Pearca and Turner, 1990).

Taxes increase costs of products and activities in a predictable manner, making it easier to judge first round financial impact on consumers and firms (OECD 2011) in comparison to permits, for which the future price can be difficult to predict. Can be difficult to determine the right number of permits to allocate as an underallocation may lead to high costs, and an overallocation can limit the ability to reach a desired level of environmental use. Regulators can use best estimates but carries environmental (e.g. irreversible damage) and economic (e.g. locking firms into technological choices) risks (Hanley et al. 1997).

On the flip side, some of these instruments (taxes, charges and auctioned permits) can generate tax revenues which can offset administrative costs, be ringfenced to finance further improvements in a target industry and potentially more distortionary taxes if used for this purpose. Revenue recycliing can play an important role in defining the overall efficiency of PMBIs, including via reducing the cost-ramp of alternative technologies. When people do not trust that a carbon price will be sufficient to reduce emissions, they prefer using the carbon price revenue to subsidise low-carbon technologies and research. The state doesn’t collect as much revenue with markets as taxes, though you can auction permits, and do so annually to increase revenues. Administered markets are generally more resource-consuming than non-market fiscal instruments, and both require monitoring.

Long-run effects

In theory and where relevant, PMBIs provide continuous incentives for further environmental harm reduction through innovation, commercialization and adoption of technologies which lower aggregate costs, because doing so saves tax expenditures.

The effectiveness of taxes are contingent on the prices of the taxed good or service (if traded) not going down which would otherwise lessen the effectiveness of prices in signaling change. Long-term cost effectiveness of price vs quantity mechanisms are affected by their responsiveness to change. This can vary in three circumstances: 1) In the presence of rapid rates of economic growth, a fixed tax leads to an increase of aggregate emissions whereas permits can give no allowance to this, but the price of permits increases to account for the enhanced desire for them; 2) In the context of inflation, a unit tax decreases in real terms and so emissions levels increases, whereas with a permit system there is no change in the aggregate; and 3) In the presence of exogenous technological change, a tax system leads to increases in control levels and a decrease in aggregate emissions whilst a permit system maintains emissions with a fall in permit prices (Stavins, 2006).

Though addressing the environmental externality, prices alone may not address the innovation market failures comprehensively as may pull through sub-optimal technologies, thereby necessitating supply-side technology instruments being introduced alongside (Goulder, 2013).

Distributional effects

Taxes can be regressive i.e. lower income groups may pay higher share of overall income to service them, though depending on revenue recycling models. Callan et al. (2009) found a carbon tax of 20 euros/tCO2 with revenue recycling in Ireland was marginally regressive, though if the tax revenue were used to increase social benefits and tax credits, households across the income distribution would be made better off without exhausting the total carbon tax. Grainger and Kolstad (2009) a Co2 tax would be 4x higher for the lower quintile of US population than upper quintile. However, design is also important. They found this wouldn’t necessarily be the case for a tax such as on gasoline which would be progressive.

PMBIs can also create hotspots of concentrated pollution which can disproportionately affect subpopulations, leading to spatially engendered inequity.

Regressive effects may not be solely restricted to households. Introducing a raw material tax might disproportionately affect those sectors that are not able to easily substitute raw materials for secondary materials. Using the OECD’s ENV-Linkages model, Bibas, Chateau and Lanszi (2021) assessed the global economic and environmental impacts of fiscal reform consisting of taxes on primary metal and mineral resources and the circulation of revenues to finance subsidies to recycled goods and secondary metal production. They found this would deliver a relative decoupling of primary material use from economic growth to 2040, with a reduction of 7% in metallic and non-metallic minerals compared to the baseline scenario alongside negligible effect on global GDP (loss of 0.2% global GDP in 2040). Regional disparities were identified, depends on whether countries were net importers or exporters of raw materials, available production technologies and input costs of primary and secondary materials.

Chateau and Mavroeidi (2020) in the study ‘The jobs potential of a transition towards a resource efficient and circular economy’, examined the consequences of a policy-driven transition towards a more resource-efficient and circular economy on employment levels across countries and sectors between 2018-40 using the structural computable general equilibrium model ENV-Linkages. The reallocation of jobs due to a package of fiscal policies was found to be limited, with net job creation globally positive but marginally, at 1.8 million, with high variability between industries and countries. Countries with large extraction sectors were found to see net-job losses, as was the case in sectors depending heavily on primary materials such as construction and some manufacturing sectors, including production of machinery and electronic equipment. Secondary metals and recyclable sectors benefited from large increases in employment. In a scenario in which only OECD countries implemented these policies, employment losses were expected relative to the baseline due to a relative loss of competitiveness.

Positive and negative spillovers

Spillovers can occur across various materials, regions, and activities.

For example, in the UK, the shift towards using “bags for life” highlights this phenomenon. A study by the Environment Agency revealed that these bags must be used at least four times to make them less impactful on climate change compared to single-use plastic bags (BBC, 2022). Similarly, the Aggregates Levy has had cross-border effects between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland due to the lack of a tax on aggregates or primary materials in Ireland (EEA, 2008), although this was somewhat mitigated by the levy credit scheme (ACLS). A 2021 report by the National Audit Office found that the Landfill Tax might have led to an increase in fly-tipping rates. In Wales, the 2016 post-implementation review of the single-use carrier bag charge found that only 13% of eligible firms reported a negative impact on their business. A study of deposit-return systems in 12 cases found no correlation between the introduction of the charge-refund scheme and sales while simultaneously driving an improvement in the quality of recyclate (Packaging Europe, 2023). The OECD (2022) has explored interactions between deposit-return systems and other extended producer responsibility (EPR) mechanisms, noting some potentially negative interactions highlighted by the industry (Packaging Portal, 2023). The MPA has also advocated for the reinstatement of the Aggregates Levy Community Fund (AggBusiness, 2021).

Strategic fit

Tax and charge-based approaches generally have low levels of strategic fit among households. The results of the third OECD Survey on Environmental Policies and Individual Behaviour Change (EPIC) published in the 2023 OECD report ‘How Green is Household Behaviour’ (OECD, 2023) found tax and charge-based approaches were the least supported policy measure by household respondents across domains including food and transport. Conversely, almost half of respondents to a 2020 YouGov survey supported an increase in the charge on plastic bag from 5p to 10p, which was then subsquently implemened (YouGov, 2020).

Public resistance to taxes can be overcome by, for instance: earmarking proceeds for other desirable uses; compensating losers using lump-sum transfers; reducing impact to possible losers by using differentiated taxes or other social cushioning measures; using environmental taxes to cut other undesirable taxes; and improving communication and information sharing to make the public feel part of the process (Carattini, Carvalho and Fankhauser, 2018).

For business, taxes may be opposed as these can cost more to regultees than prescriptive regulatory approaches. Markets are generally more politically desirable than taxes - with there less fear that government will abuse the system for revenue generation ends, the polluter pays only for the non-optimal portion of total emissions (though not always) and can feel more in control of a permit system (Pearce and Barbier, 2000).

Reductions in the current tax regime such as on VAT, capital allowances and too subsidies are least preferred options by government authorities due to reductions in tax receipts and exchequer costs.