Selection criteria for policy tools

This page outlines how policy tools link to government objectives and criteria for comparing between policy options.

Linking policy tools to policy objectives

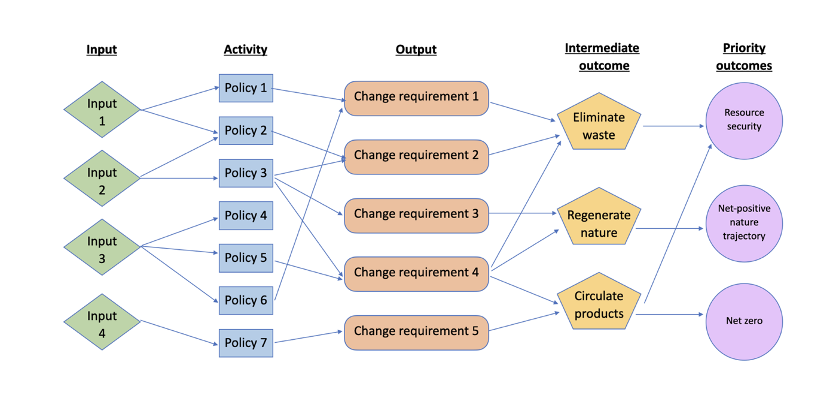

Logic models are often used to represent the theory of how an intervention and its inputs can contribute to outcomes and impacts by addressing key drivers of performance (OHID, 2018). Logic models can be made up of components such as the following:

Input: Something put into a process, project or change e.g. monetary or operational resources;

Activity: What is done with the inputs to produce the intended outputs e.g. the introduction of policy or establishment of a research programme like NICER;

Outputs: Goods and services produced from inputs which result from the completion of activities;

Intermediate outcomes: Changes resulting from outputs as the first outcomes observed (e.g. increased reuse in the economy); and

Strategic objectives/priority outcomes: The real-world (and generally, longer-term) impact the department is seeking to achieve e.g. a more resource efficient, low waste and low emissions economy.

Illustrative logic model

To be robust, logic models need to have their assumptions grounded in evidence (HMT, 2023). Even where so, logic models models should be understood as simplifications. ‘Systems mapping’ is an increasingly incorporated part of the option identification process, and can help identify dependencies between policies, barriers and contingencies on other actors at an early stage (Barbrook-Johnson and Penn, 2022; Government Office for Science, 2023).

Where policies can focus

While policies focusing directly on the flows and stocks of materials are often seen as most directly relevant to the CE, policies in adjacent or supporting areas can also important to achieve CE-related outcomes. Policies of potential relevance to the CE can broadly be separated into different ‘domains’ of focus, and in particular, whether they are levied on:

Other policy domains of indirect relevance to CE objectives include those relating to human health e.g. the UK ban on asbestos, which has helped reduce risks and barriers to construction waste recovery activities.

Policy rationale - tackling barriers and failures

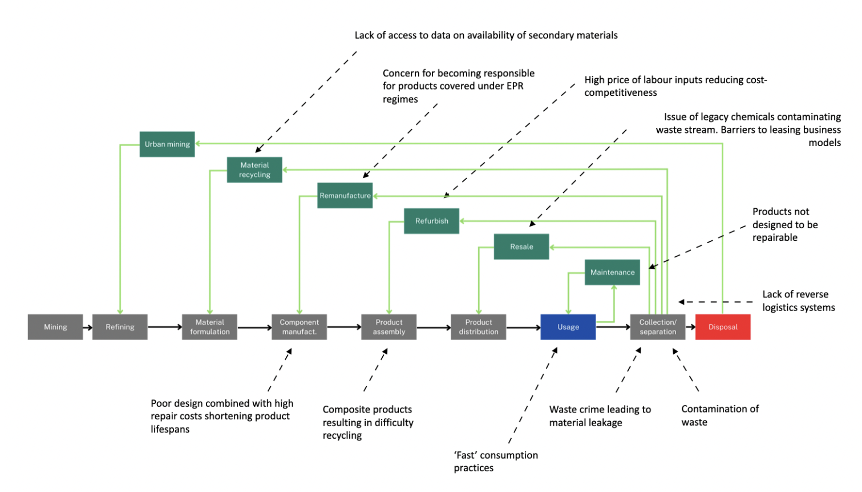

Barriers are things that restrain change towards a particular outcome. These can represent elements of the status quo which if not managed, can delay or limit change and in some cases indefinitely (OECD, 2009). Barriers to CE implementation can arise in many forms across economic, policy, technological, social and operational dimensions and can differ or overlap across products or value chain stages. Introducing regulation without consideration of these can lead to reduced effectiveness and deadweight loss.

As an example, barriers to the expansion of domestic recycling capacity have been noted to include relatively lower prices for exporting waste (which is treated as equivalent to domestic reprocessing in current regulatory frameworks) and the volatility of recycling note values in existing packaging recycling note markets and resultant uncertain returns on investments (Iacovidou et al. 2020 in OECD, 2022). Further examples of possible barriers along the value chain are outlined in the figure below.

Examples of barriers along the value chain

The grounds for introducing policy is sometimes thought about in terms of responding to a particular framing of barriers - ‘failures’. These are described further below.

Criteria for instrument selection

Key questions that policy-generating government departments may have in the longlist process of policy options include what is the alignment of an option to strategic objectives of the department and what are the critical interventions needed to deliver required changes, their likely effectiveness, feasibility and affordability. Policy instruments can differ in their effectiveness and efficiency in achieving medium and long-term policy objectives, meaning the choice of instrument can be a key factor to consider additional to measures sought to be driven. At the longlist appraisal stage therefore, policy options (a combination of both a measure and policy instrument) can be assessed against a set of criteria or ‘Critical Success Factors’ (CSFs) i.e. ‘attributes essential to the successful delivery of projects and programmes’ (HM Treasury, 2023a). Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) can be used to facilitate the consideration of multiple criteria in decision-making.1Examples of relevant CSFs are outlined below.

Policy mixes and interactions

Instrument choice can be consequential for overall costs and benefits of pathways, risk management, spillovers and immediacy of impacts, among other dimensions (Berestycki and Dechezleprêtre, 2020). Policy issuing government bodies can have a choice between discrete instruments or an instrument ‘mix’. All policy instruments have strengths and weaknesses and differ in their suitability in relation to given policy objectives, while none have the ability to address every aspect of developing a more circular economy on their own. This is often the case even for individual product groups e.g. textiles (WRAP, 2023). This implies that policies to support a circular economy are likely to need to be introduced as a mix, levied also at different scales (del Rio and Howlett, 2013; Wilts and O’Brien, 2019). In the UK, new policies are also not introduced in a vacuum and will interact with existing legislative and regulatory requirements.

Pro-environmental behavior encompasses choices and actions that reduce environmental impact or improve the environment (West and Michie, 2020). The COM-B model, which consists of Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation, is one of several behavior models used to understand and influence behavior. Other models also exist, each offering unique insights and approaches. In the context of government tools for driving change, the COM-B model classifies these tools into three categories:

- Enhancing capability through knowledge and skill development

- Increasing opportunities for desired actions, such as infrastructure provision and financial support

- Boosting motivation for desired behaviors

The COM-B framework suggests that policies should combine these elements to create conditions for desired actions. For example, an effective recycling policy may require businesses to have the capability, opportunity, and motivation to recycle (Defra, 2018b).

A 2007 OECD study found a mix of instruments were not always better than a single one for delivering environmental outcomes efficiently. Therefore, when developing a policy response, diversity of instruments for diversity’s sake should be avoided (Gunningham 2009). Where there is a sound basis to introduce policies alongside one another, these need to be leveraged within a coherent framework across the lifecycle of materials, products and services to be efficient, in addition to the system in which those materials and products operate. Certain instrument mixes such as EPR and taxes, which can be additive in nature or environmental tax and subsidy reform, may offer greater complementarity than others.

Coherence with the wider policy landscape is also key, particularly with policies for delivering ‘net zero’ and industrial strategy. Complementarities and conflicts between instruments and broader considerations such as performance against critical success factors and alignment with existing domestic cultural, legal, technological and policy arrangements can be considered to ensure policies do not combine to be less than the sum of their parts (Howlett, 2004).

Sequencing

The sequence in which instruments are introduced as part of a policy pathway can have implications for aggregate costs and benefits given the potential for interactions. For instance, while certain instruments such as taxes might help reach near-term objectives, technology-push policies might need to be introduced concurrently to bring new technologies to the shelf without which more ambitious long-term objectives may not easily be met (Sandén and Azar, 2005).

Different schools of thought exist on best sequencing approaches. Bleischwitz (2010) calls for a step-by-step approach to policy introduction addressing market failures first. ‘Smart regulation principles’ recommend a responsive approach, whereby instrument choice is escalated from combinations including least interventionist approaches to those which involve a higher degree of coercion based on responsiveness of regulatees (Gunningham, 2009). Marginal abatement cost-curve (MACC) approaches propose starting with policies with least net cost and expanding out. Criticisms of MACC-based approaches relate primarily to overlooking temporal interdependence between policies, however. For instance, Grubb and Wieners (2020) illustrate a slow carbon price ramp approach is likely inefficient in the case when carbon abatement costs are shaped by innovation. In this case, higher cost options may be more effective to start with if they drive down innovation over time, and therefore reduce cumulative costs.

Footnotes

The recommended method for longlist appraisal in the Green Book is a Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) approach using factors whose weights are defined through swing-weighting. Such an approach can be used to provide an overall score to policies based on how they score against individual CSF in combination with weights applied to each CSF which are intended to represent the perceived importance of that criterion.↩︎